Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Lawmakers, advocates push to keep Mental Health First Aid training

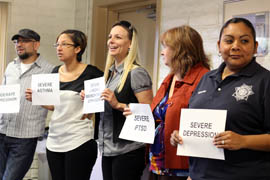

TUCSON – A dozen or so people circulate around a conference room at the Community Partnership of Southern Arizona, each holding a paper with a physical or mental problem written on it in black marker.

One person represents severe vision loss, another epilepsy. Others’ conditions include moderate depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia and paralysis. The goal: Get their conditions in order from least to most severe.

It takes several minutes – and assistance from session leader Mark Haley, training coordinator for Hope Inc. – to get the group in the correct order, with gingivitis at one end and severe dementia at the other.

Haley tells the group that while every person’s experience differs, mental health challenges can be just as debilitating as physical ones. But oftentimes mental health problems are much less understood.

Marissa Richard, a U.S. Air Force sergeant who’s holding a “severe asthma” sign, notices that a woman representing PTSD is just two spots closer than herself to the most severe end of the spectrum. She expected it to rank with severe depression, schizophrenia and dementia among the most serious conditions.

“Maybe it’s because I’m in the military,” Richard said.

These participants, most of them public health workers, came here to learn about mental illness and how to help those suffering from it. The course is called Mental Health First Aid.

Much like CPR training, the free 12-hour class, taught over two days, teaches how to recognize and react when someone experiences anything from an eating disorder to thoughts of suicide.

The state began offering Mental Health First Aid courses in 2011 after the Tucson shooting that left six dead and wounded U.S. Gabrielle Giffords and 12 others. Since then more than 3,500 people have received the training at no cost.

Despite what officials and advocates call a successful start, Arizona’s Mental Health First Aid program could end in the next few months. A federal grant that made it possible is running out.

State Rep. Victoria Steele, D-Tucson, who is a licensed counselor, said Mental Health First Aid can turn the public into a front line of defense against community violence stemming from mental health challenges.

“We can start talking about preventing shootings, we can talk about guns, and that’s fine,” Steele said. “But I think what we really need to do is back up and talk about … how to prevent people from getting that desperate.”

An appropriations bill by Steele and seatmate Rep. Ethan Orr, a Republican, whose district includes the site of the Tucson shooting, sought $250,000 to continue Arizona’s program. It failed, but as of late April Steele and Orr were working to get funding into the state budget.

“What I see in my district is people are hungry to see people come together for rational solutions,” Orr said. “Mental illness is not a partisan issue, it’s really a community issue.”

Steele said if the program ends it would be a devastating loss to the behavioral health system and the public.

“We know that prevention and treatment work,” she said. “We know we can prevent future deaths.”

An expanding profile

Mental Health First Aid originated in Australia in the late 1990s, the brainchild of Tony Jorm, a mental health professor, and his wife, Betty Kitchener, a Red Cross first aid trainer.

According to the website for Mental Health First Aid Australia, Jorm and Kitchener were walking their dog when they hit on the idea of combining the principles of first aid training with mental health intervention.

The program launched in that country in 2000 and quickly garnered international attention. Since then, it’s been adapted for use in 20 countries.

State health officials in Maryland and Missouri, along with the National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare, coordinated with experts in Australia to create Mental Health First Aid USA in 2007.

“We can define Mental Health First Aid as an early intervention program,” said Susan Partain, director of Mental Health First Aid operations for the National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare, which oversees the U.S. program. “It’s about encouraging people earlier on to get help.”

The U.S. curriculum covers everything from substance abuse to psychosis and teaches how to connect those with mental health problems to the resources they need.

“What it’s really designed to do is present accurate information about mental health, decrease stigma … and really equip people from all walks with the skills to identify somebody with a mental health crisis,” said Steve Nagle, training specialist for Community Partnership of Southern Arizona.

At the Tucson training session, participants learned a five-step action plan that includes assessing risk and giving a person who is experiencing a health crisis information and encouragement to get professional help.

“Mental Health First Aid is not about diagnosing people,” Nagle said. “It’s also not really about curing people. It’s about providing that bridge for services.”

Organizers say Mental Health First Aid saw a rise in interest across the country after the December school shooting in Newtown, Conn., that killed 27 people, 20 of them children. President Barack Obama’s plan for addressing gun violence included the program among mental health care initiatives aimed at students and young adults.

In January, U.S. Rep. Ron Barber, D-Tucson, who was wounded in the 2011 Tucson shooting, introduced the Mental Health First Aid Act to provide an initial $20 million in federal grants to states and organizations to provide the training. He cited the success of the program in his district and the need for intervention.

“If people had known more about mental illness with Jared Loughner … I think there may have been more attempts to intervene,” Barber said.

Then Mental Health First Aid funding was incorporated in Obama’s proposals on gun violence and legislation introduced in the Senate. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid placed the bill on hold in late April, however, after legislation to expand background checks on gun purchases failed.

“I think the community certainly has seen the benefits,” Barber said. “It’s certainly not a cure-all, but it’s a big step.”

In Arizona

Claudia Sloan, communications director of the Arizona Department of Health Services’ Bureau of Behavioral Health Services, said the the Tucson shooting brought attention to the need for better awareness of and help for those suffering from mental illness.

“Early intervention can make a big difference in a person’s treatment and recovery,” Sloan said. “If you’re able to identify a mental illness or a mental health issue early … the larger your chances are for successful treatment and recovery.”

Less than two months after the shooting, the state obtained the federal grant money and organized training for Mental Health First Aid trainers. Sessions, which began shortly after around the state, have catered for the most part to behavioral health professionals and educators.

Sloan estimated that it costs $25 to train a person in Mental Health First Aid. Up to this point the course has been offered for free to anyone who wants to take it.

The ultimate goal is to train every Arizonan, she said, though that isn’t possible with the money currently available.

“That would be a dream,” she said.

To this point the state’s program has spread mostly through word of mouth, with trainers publicizing training sessions mainly to those in public health. However, Sloan said her department would like to launch a statewide public awareness campaign to encourage more people to participate.

“The program has grown at a slower rate because the resources allocated have been, you know, small resources,” she said.

But that hasn’t prevented Arizona from becoming a leader on the national level.

The National Council on Community Behavioral Healthcare estimates that there are more than 80 certified Mental Health First Aid trainers in the state. And Arizona ranks 10th nationally in its percentage of residents trained in Mental Health First Aid.

Partain, with the council, said Arizona has about the same numbers of trainers and trainees as Maryland, which was one of the first states to have the program in the U.S.

“Overall, Arizona is definitely one of the strong states that we have with the program,” she said.

Arizona was also one of the first states to begin offering the Youth Mental Health First Aid curriculum last fall. The program teaches a slightly altered curriculum geared toward those who live and work with children, including parents, teachers and coaches. It’s one of a growing number of specialized programs offered by Mental Health First Aid USA.

Krysta Laureano, a Youth Mental Health First Aid trainer at the Family Youth Involvement Center in Phoenix, said the program is especially important since the majority of mental illnesses appear between the ages of 12 and 25.

“Sometimes parents get very wrapped up in the chronic behaviors that they have with a child,” Laureano said. “It’s those little people – the lunch lady, the school bus driver, the janitor – it’s those people that tend to see that maybe this behavior isn’t normal.”

Decreasing the stigma

The tragedy in Newtown, Conn., reignited the national conversation about mental health even though the shooter, Adam Lanza, was never diagnosed with a mental illness.

According to his family, Lanza suffered from bullying in high school and had an form of autism known as Asperger’s syndrome.

Advocates like Jim Dunn, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness in Arizona, are quick to point out that connecting mental health problems to violence can be a dangerous stereotype.

“These really are folks that have a tough row to hoe,” Dunn said. “They aren’t as scary as people make them out to be. We need to keep people engaged in treatment and care.”

Dunn said Mental Health First Aid helps decrease the stigma surrounding mental illness by steering the public conversation away from guns and violence. Mental Health First Aid helps improve people’s access to services and gives the public accurate information about mental illness, he added.

“I think we definitely need something like this,” he said. “We know that treatment works.”

Both independent researchers and the creators of the course have completed more than a dozen evaluations of the program. Much of the research so far has been led by Tony Jorm, who developed the Mental Health First Aid program and now works as a professorial fellow at Orygen Youth Health Research Centre at the University of Melbourne.

According to Jorm’s article published in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry in 2011, research has consistently shown that the course increases knowledge about mental challenges. It also improves attitudes towards mental illness and decreases stigma, while evidence of the positive effects has been found even a year and half after completing the course.

Elaine Groppenbacher, a priest with the Ecumenical Catholic Communion, took the course as a part of her seminary program at the Claremont School of Theology in California. She works in three parts of the Valley with very different demographics – north Phoenix, just south of downtown Phoenix and Tempe – but finds the training useful with residents of each area.

“All three have people within in their communities who live with mental health challenges or are victims themselves or have family members who are,” she said. “They are hungry for the education, they are hungry for the tools.”

Groppenbacher said though many people go to family, friends and clergy members when facing a mental challenge, almost none immediately seek or have access to professional help. She said Mental Health First Aid would help clergy and other community members be better prepared to help those struggling with mental problems.

“As much as they want to help, they don’t have the power,” she said. “I think this will give people the courage.”

Sgt. Jim Kirk and others from the Tucson Police Department came to the Capitol to speak in support of the bill to expand Mental Health First Aid in Arizona. Kirk compared the course to community watch programs.

“We’re training the community in what to look for, to educate individuals as far as mental illness symptoms … so we can be on the front end of some of these things before they become violent,” he said.

At the Capitol

Rep. Ethan Orr, executive director of a nonprofit that helps disabled people find jobs, said helping the mentally ill also helps the public.

“I’ve seen the front lines of how mental illness impacts people’s lives,” Orr said.

Along with Rep. Victoria Steele, he called expanding Mental Health Health First Aid a personal issue. Both freshmen, they started working on the legislation shortly after winning office.

“This became our way of helping people, of helping people who might be suffering from mental illness and may not even know it,” Orr said.

As introduced, HB 2570 would have appropriated $500,000 to expand Mental Health First Aid. An amendment reduced the amount to $250,000 before the House overwhelmingly approved the bill.

But the bill stalled when the Senate Health and Human Services Committee didn’t take it up.

“We were very surprised and enormously disappointed because this means a lot to both of us personally,” Steele said.

As of late April, she and Orr were trying to get funding for the program included in the budget as a line item. But the budget remained in limbo as GOP lawmakers wrangled with Gov. Jan Brewer over the governor’s plan to accept billions in federal funding to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

“It would have been nice to be able to say that we did it,” Steele said. “But what really matters is that we get this program in.”

The future

Trainer Mark Haley said though the future of the Mental Health First Aid isn’t clear, its impact certainly is.

“I definitely see this as a benefit that goes back to our community, the masses,” Haley said.

He said he’d like to see the program take off at colleges and schools to help younger people facing mental health challenges.

“Educate people when they’re young and death rates tend to decrease,” he said. “As long as they take away our action plan and learn how to apply that, it will make such a difference to our community.”

Amanda Jo Durante, a living skills coach who took Haley’s class, said her firsthand experiences with mental health challenges gave the class personal significance.

Durante said her father suffered from addiction and that she helped her mother battle through severe depression.

“If I would have taken this class … then I think I would have been more prepared, I would have felt more confident,” she said. “It would have been less scary.”

Claudia Sloan said the Arizona Department of Health Services would like to teach more Arizonans to face mental illness without fear – but would need funding to make that possible.

“Mental health, it’s a public health issue,” Sloan said. “It’s just as important as a physical condition; in fact, you probably have a higher chance of encountering somebody with a mental illness … than you have encountering someone suffering from a heart attack.”